Your social impact network is always at risk. Even for a seasoned network lead, the risks of guiding a collective impact model can make you shiver with uncertainty. From member disengagement to misaligned goals and competing interests to network failure, there’s a lot to ensure goes right to meet your shared mission.

What if I told you that you can take steps right now to boost your network’s health?

If you’re feeling unsure about your network’s collaboration, goal-setting, or overall progress, it may be time to step back and rethink how your nonprofit network fits with your shared social problem—and why working together may be the best solution. Your social impact network has the potential to make a bigger difference. So, how can you start working more effectively toward progress and keep that progress going?

Revisit the social problem.

When your progress seems uncertain, a great first step is to recenter on the problem you originally aimed to solve. Revisiting the social problem at hand can remind your network of the “why” behind your original coalition. But is your original “why” still relevant to the actual issue?

Using root problem analysis can help your network realign your “why” with the social issues needing support. It’s not complicated, either. I like to think of it in four steps:

A situational analysis. Each network member has essential data that tells a unique story about the overall social issue. When combined, all this data can help you jointly determine the main problems your network is seeking to target.

Prioritizing the issues. Identify common themes and group problems accordingly. For example, are similar populations, resources, or methods shared across certain problems? By grouping your problems in buckets, you can start to tackle them from a higher level.

Map the issues. There are three main methods of mapping network problems: Five Whys, Fishbone Diagrams, and Root Cause Trees.

The Five Whys method is best for working with complicated problems and one group of issues, starting from a broad problem statement and drilling down. After defining the problem from the groups of issues in Step 2 the group asks: Why is the issue happening? Then, Why is that surface cause happening? Why is the possible root cause happening? Addressing issues in this way can help you move past the surface and find the underlying social problem affecting your target communities.

Fishbone Diagrams are a fantastic visual method for mapping complex wicked problems where the causes are not as clear. The overarching problem from Step 2 is placed at the “head” of the fish on the right, from which categories of the causes are branched off on a diagonal, like the dorsal fins on a fish. Primary and secondary causes of these categories can be added to illustrate the problem’s complexity. Take, for example, the below Fishbone Diagram mapping increasing childhood obesity:

Root Cause Trees are best for mapping multifaceted, persistent problems with significant research buzz. Taking surface causes from Step 2, these diagrams identify multiple layers of possible root causes. Take the childhood obesity example again:

Define the type of problem. There are four rungs of the social problem spectrum. On one end are simple problems, which are straightforward, with a clear solution that can be solved by one organization. On the other end are chaotic problems, ones that evolve so rapidly that intervention has a hard time with upkeep. In the middle are complex and complicated wicked problems, in which a coordinated networked response is most appropriate due to their systems-level approach.

When defining the problem your network faces, it is important to ask: Is a network the best solution? With simple problems, a network may be too costly. With chaotic problems, network capacity may not be sustainable. So, when your problem falls outside of the complex or wicked categories, consider if your network is approaching an issue worth the investment.

Re-evaluate your stakeholders.

With multiple organizations working toward their own goals, it can be easy for folks to lose touch with the bigger goal the network is aiming to achieve. Whether you are facing hardships with resource-sharing, a change in leadership, or meeting network goals, you can take a quick audit together to find opportunities for improvement:

- Where can we diversify network revenue and resource streams? Will creating a new organization help obtain them?

- Are network stakeholders confused about where to put their efforts? Will new network goals recenter the network??

- Is the network making progress toward its mission? Have new issues come forward since the network’s start?

Answering these questions may need some outside perspectives. Consider gathering target population volunteers from each network partner to help consult on providing the best impact. Community engagement focused on long-term relationship building can help your network gain traction on direct action, informing your approach toward sustainable impact.

Map the actors working toward your goal.

Sometimes, reframing your network’s purpose can seem ambiguous. Especially due to conflicts of interest, a network partner can still lose involvement if their role in the mission does not have a clear mutual benefit. Finding that benefit can be crucial to strengthening ties, and actor mapping can do just that.

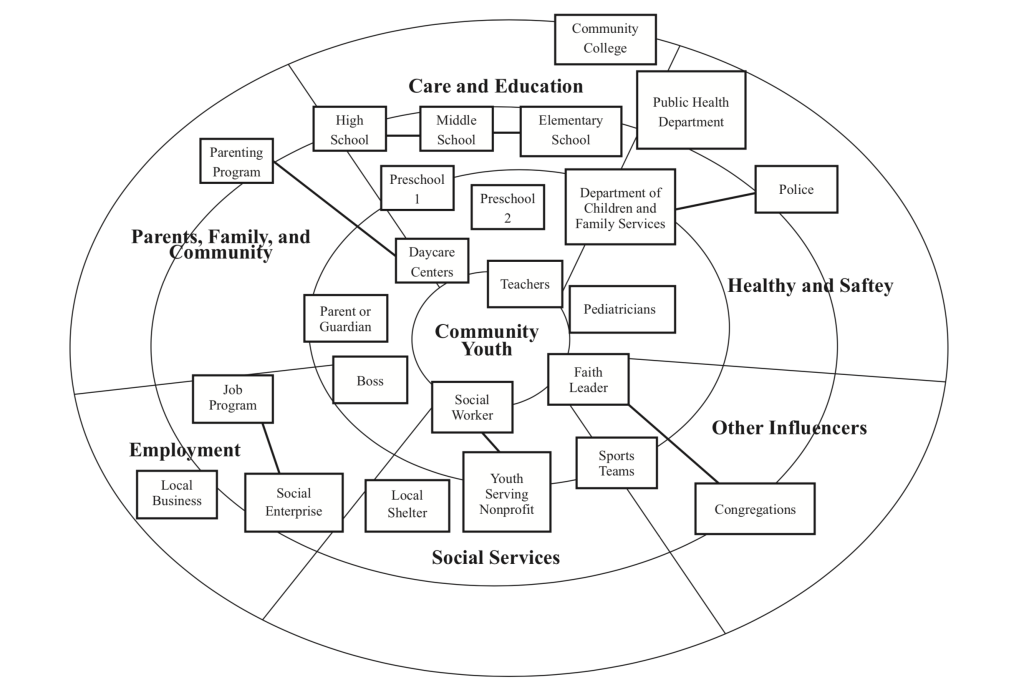

Actor mapping allows network partners to see the full picture of the social problem and how everyone fits in to make an impact. It can be fun, easy, and enlightening. Take for example, the actor map below:

For community youth, there are a number of ways to make an impact. Finding where each organization fits into the underlying services to a larger problem can show how partners can provide for the mission of the network without compromising interests. Even the constituents you involve in your community engagement can be mapped to fill in the gaps your network doesn’t directly impact.

- Draw a large circle with a smaller circle in the middle. Place your social problem central to your network efforts in the smaller circle.

- Brainstorm notable elements of your social problem that would need to be addressed for change. These should be the pie slices of your larger circle, outside of your smaller circle.

- Name the important network roles, settings, and organizational actors, placing them on sticky notes. Place the sticky notes in their appropriate pie slices.

- Draw lines between the notes, illustrating the network’s existing collaboration toward the central problem.

- Identify groups of actors that form commonly understood areas of influence. In the example above, consider children’s media networks or education companies.

Step back and evaluate. Where can your network build collaborations, narrow its focus, recruit to fill in the gaps, or expand into other networks? Actor mapping can help you be more informed as a network leader, motivating you to strategize accordingly.

Get the word out.

Once you’ve recentered your social impact network, it’s time to make it public. Network legitimacy can help strengthen your reputation among constituents and stakeholders alike, providing you with opportunities for more resources and visibility.

Build a name, a website, and a newsletter if you don’t have those already. Align with messaging across network partners. Becoming recognizable to your members and community as a formal coalition can help the network seem necessary and valuable to all involved. Showcasing value can get the ball rolling on funding and capacity-building, allowing you to make a better impact.

With a legitimate, aligned, and involved network, each partner can contribute to a mission that makes a difference and lasts to serve.

These are just a few examples of how to get started brainstorming in the face of change. You can find more detailed tools and examples in my book Networks for Social Impact.